On Field Recording

200x: Setting up to record a local punk show, I get into an argument with a friend about mic placement. I’ve been reading a translation of Herman von Helmoltz’s On The Sensations of Tone as a Physiological Basis for the Theory of Music, and I have opinions about the acoustics of the room. I try to explain something about early reflections through a haze of cheap alcohol and gray market SSRIs, but I don’t know what I’m talking about. Neither does my friend. One thing we have figured out, more from repeated practice than from reading 19th century German physics, is that an audio recording isn’t just a record of an aural experience but something new, a transduction. What we can’t agree on is what that new thing should sound like or how we should get it to sound that way. We end up splitting the difference on mic placement. The band sounds like shit but the recording is worse. We emerge from the noise and the dark feeling victorious, like we’re moving toward something huge and important.

1942: Pierre Schaeffer and Jacques Copeau found the Studio d’Essai, which functions both as an experimental art collective and a radio broadcasting apparatus for the French Resistance to Nazi occupation. Schaeffer’s experiments with new technologies for recording and broadcasting at Studio d’Essai lead him toward a new theory and practice of music.

c. 500 BCE: Pythagoras teaches from behind a curtain. His students listen attentively to the sound of his disembodied voice. After Pythagoras’ death, the more devout and dogmatic of his pupils come to refer to themselves as the akousmatikoi, the hearers of Pythagoras’ oral teachings. Their community and tradition is way of listening.

1913: German philosopher Edmund Husserl publishes his Ideas: General Introduction to Pure Phenomenology. In seeking a pure consciousness of absolute being, he develops the concept of phenomenological reduction through the practice of epoché: a kind of cognitive bracketing that allows for the direct perception of phenomena without preconception about their source or underlying nature.

1969: Stevie Wonder releases Stevie Wonder’s Journey Through “The Secret Life of Plants”, an album about a movie about a book about plant sentience. He is the first artist to use the Computer Music Melodian digital sampler.

1945: Maurice Merleau-Ponty writes “To return to things themselves is to return to that world which precedes knowledge, of which knowledge always speaks, and in relation to which every scientific schematization is an abstract and derivative sign-language, as is geography in relation to the countryside in which we have learnt beforehand what a forest, a prairie or a river is.”

2017: Having sold or abandoned most of my belongings to escape a bad situation back in Oklahoma, I find myself sitting next to the Willamette River with a notebook, a pen, and my Zoom H1 Handy Recorder. I feel at peace for the first time in months. I press the big round record button on the front of the Zoom and I begin to write. The recording, the river, the feeling I have there, will be the basis for A Confluence (A Baring Of Teeth), my first new composition in two years.

1948: Pierre Schaeffer coins the term musique concrète for his new music. At its core is a theoretical concern with a kind of auditory epoché, an experience of sound objects themselves removed from preconceptions about their source. Shaeffer calls this acousmatic listening. By divorcing audio recordings from their recognizable contexts—through isolation, reduction, manipulation, and repetition—Schaeffer seeks to reveal their inherent musicality.

1969: The Winstons record Amen, Brother.

1972: R. Murray Schaeffer, working with the World Soundscape Project, conducts a series of field recordings in Vancouver. Schaeffer and the WSP are concerned with acoustic ecology and the pollution of the natural soundscape by urban noise.

2021: Norman W. Long releases Black Space in Winter, recorded at Marian R. Bynes Park on the southeast side of Chicago. He writes: “These recordings offer us a way to listen to communities of color by listening for the ecological, economic and residential life that make up the community. Bird song, trains at the Norfolk Southern Calumet Rail yard arriving, departing, connecting, loading and unloading, traffic from 103rd St and neighbors bordering the east side of the park comprise the soundscape. I am also recording (with relatively affordable handheld devices) in a public space that can facilitate the health and resiliency of the ecology and local residents, as a member of the community and as a Black man economically affected by this pandemic.”

1908: The sky explodes over the Middle Tunguska River, leveling 800 square miles of surrounding forest. The cause is unknown. Witnesses describe the sound as like thunder, like cannons, like stones falling from the sky, like dozens of trains.

1986: Salt-N-Pepa sample the Amen break on the track I Desire, from their debut album Hot, Cool & Vicious. The six second loop will become one of the most sampled sounds in music history.

1988: Pauline Oliveros climbs down into the Dan Harpole Cistern at Fort Worden State Park, Washington. The massive underground chamber has a 45 second reverb. It does weird things to sound. She coins the phrase Deep Listening.

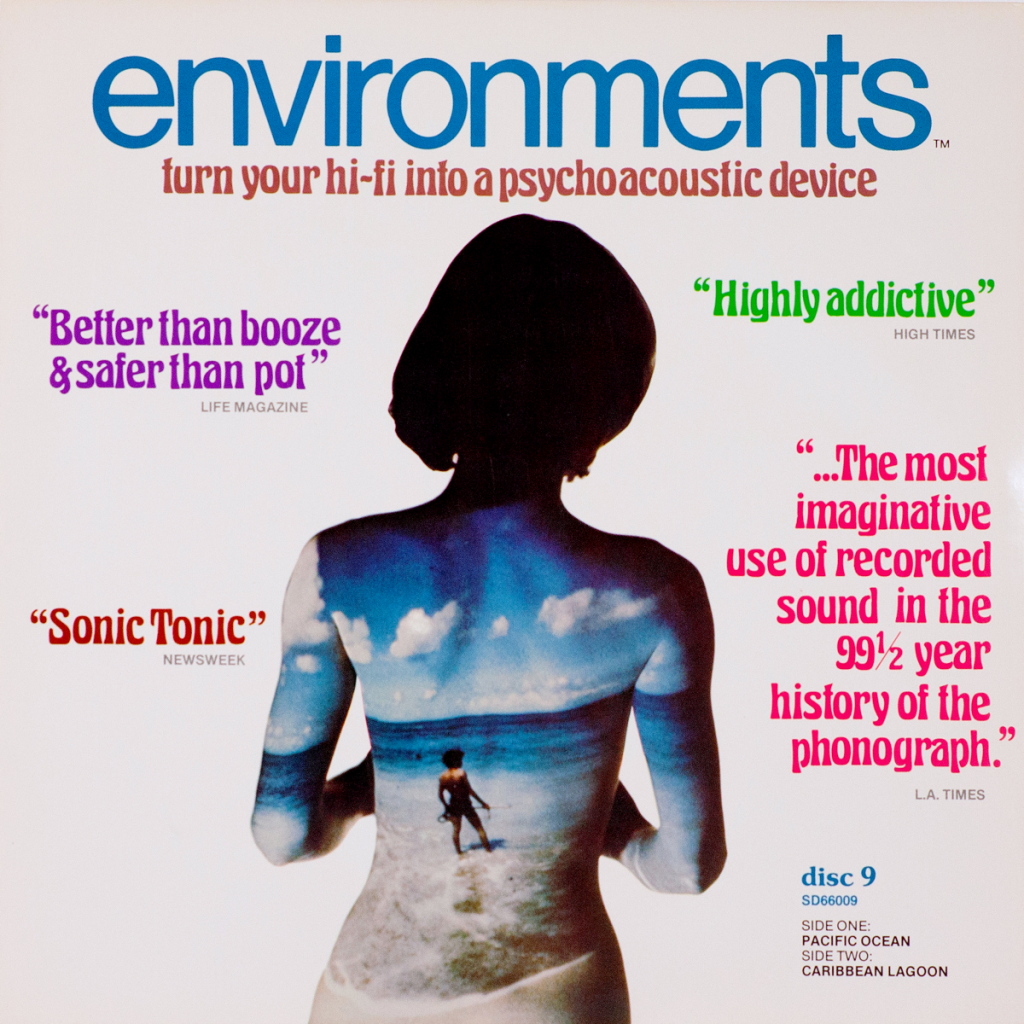

1968: Irv Teibel collects a series of field recordings of ocean waves at Coney Island beach. He plans to sell them as a new kind of music, a sort of aural vacation, but his recordings don’t have the desired effect on playback. A recording of the beach is not the sound of the beach, nor is it the idea of the beach, nor is it the beach in itself. Teibel relies on extensive digital editing of the original recordings to produce The Psychologically Ultimate Seashore. Finally satisfied, he releases the recording as the first in his Environments series, proclaiming: “The music of the future isn’t music.”

1975: World Soundscape Project documents the soundscapes of five European villages. Their purpose “is to enquire into the different types, quantities and rhythms of sounds heard in five villages in five countries, and to show the relationship of these sounds to the structure of each village and its life.” They release their recordings and accompanying analysis as Five Village Soundscapes.

1989: The Deep Listening Band releases Deep Listening.

1997: The United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration records The Bloop. Originating deep in the remote South Pacific, the sound is loud enough to be heard for thousands of miles. Its source is unknown at the time of recording.